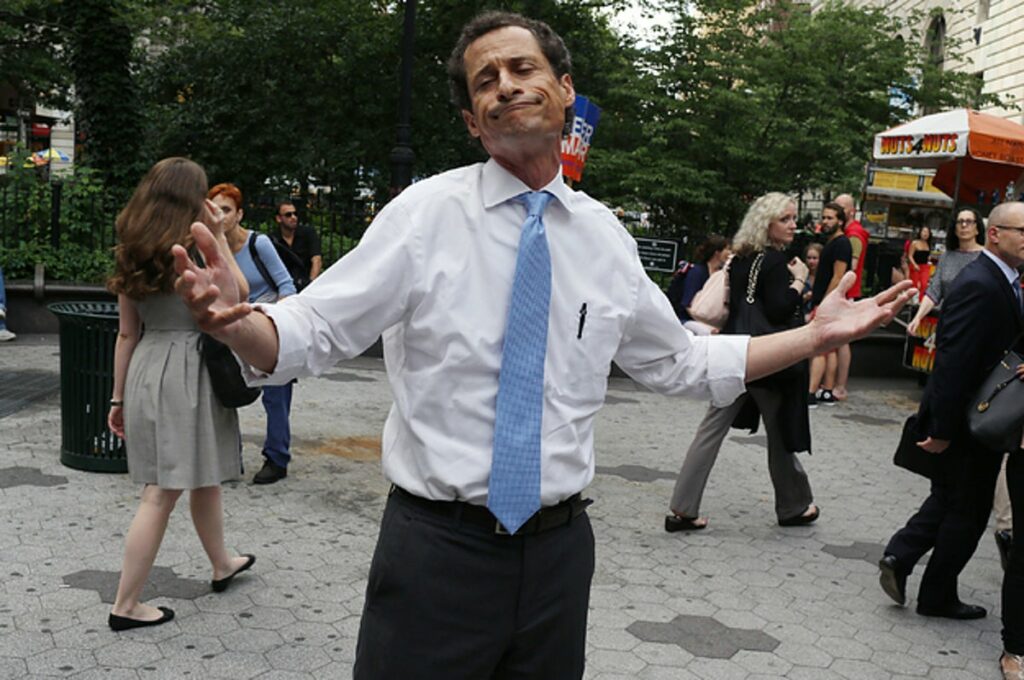

“I hope that one of the things that people are going to see in the campaign and also if I’m fortunate enough to be mayor is that I’m going to do the job with a smile on my face,” Weiner said. “Sometimes it feels like Mike Bloomberg is getting a root canal when he’s in the Blue Room.”

Anthony Weiner has been holding himself in these days.

“Apparently, funny isn’t in like it was in 2005,” he said. “Now angst-ridden is in, so I’m doing that this year.”

This was a joke. A quiet joke, an increasingly rare public joke-not quite the kind of laugh line as any of his hot dog slogan jokes during the 2005 race, or the more raunchy play on his name that he used to use as mock enticement while campaigning at the Gay Pride parade.

Three years after his first run for mayor, a year before his second, this is who he is now, who he has developed into being, and who he has forced himself to become.

He is not as funny as he once was. And without a popular, millionaire incumbent in the race, his new campaign for mayor is not at all a joke.

“It wouldn’t be fair to characterize this as a six-year plan to become mayor or anything like that,” Weiner said, reflecting on all that has happened since 2005 in a diner a few blocks from his home in Forest Hills. Breakfast that day is a waffle covered in butter and syrup, carefully cut into quarters along the lines and eaten with his hands. He has a cup and a half of coffee, poured over a large cup of ice, and, at the waitress’ prompting, a small glass of orange juice, because, he reflects, that is probably good for him.

About 250 votes separated Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer from the 40 percent he would have needed to avoid a run-off. All through that night and campaigning at a subway stop in Harlem the next morning, Weiner-who came in a distant second, 10 points behind-planned to continue the fight, even though most of his top advisors had already recommended he leave the race.

He could have waged a protracted battle with Ferrer’s campaign over counting absentee votes, and dispatched staffers to the Board of Elections the next morning preparing to do just that.

He might have lost. He might have won.

Instead, he quit, sparing Democrats the kind of divisive, potentially racially charged primary that had eviscerated the party in 2001, and sparing himself a run against the popular mayor who was already by that point pouring millions into the race.

Suddenly, the wisecracker was a statesman. Suddenly, the scrappy underdog was the frontrunner for 2009.

Weiner himself tried to play down the strategizing that went into the decision. Maybe he would have won the run-off, he said. Maybe he would have beat Bloomberg. But his only interest at that moment, he insisted, was keeping the Democratic Party united and conceding a defeat he had already himself accepted.

“People stop me all the time and say, ‘You should have run,’ ‘You should have kept at it,’ or ‘You would have beaten him,’ or something like that. And then there are people who say ‘Great job,'” he said. “And I’m like, ‘Dude, I lost.'”

He may not have gotten the nomination. But, most political observers agree, he certainly did not lose.

Back in Washington, Weiner looked over his campaign agenda again. Gradually, he began crafting laws that accomplish similar things to what he had talked about when running.

“The campaign ended, but it was part of a continuum of me trying to get these things done,” he said.

This included revisiting his middle class tax cut. He introduced and has since re-introduced the Middle Class Tax Relief Act, legislation which would provide a 10-percent tax credit and doubled child tax credit for people with joint returns of $150,000 or less, eliminate taxes altogether for those with joint returns of $25,000 or less and eliminate the alternative minimum tax for those with joint returns of $225,000 or less. The cuts would be paid for with a tax surcharge on people making over $1 million annually.

A year later, the bill remains in the Ways & Means Committee, where it is apparently not a top priority for Committee Chairman Charles Rangel (D-Manhattan).

“I think Anthony Weiner’s a wonderful legislator,” Rangel said, “but we have not discussed any of his issues which concern taxes, or Ways and Means issues.”

Weiner has introduced 42 bills in the current Congress-more than three times the average for representatives, and well ahead of most of the New York delegation. But only an amendment providing $1 million in additional funds to the National Park Service has passed.

As with the stalled tax legislation, Weiner blames this mostly on not being able to find common ground between his own progressive agenda and what George W. Bush would be willing to sign into law.

But that has not stopped him from trying. Weiner has specialized in legislation aimed at larger homeland security improvements and at providing more targeted benefits to New York, from his proposed AmeriCorps-administered GothamCorps to his now-progressing effort to reopen the Statue of Liberty crown.

Often, the bills take on both, as with one which would revive the Clinton-era C.O.P.S. program, providing funds to hire up to 50,000 new police officers nationwide.

Then there is a bill to limit the fees charged by check-cashing businesses, or another to prohibit any drug manufacturer from having a controlling interest in companies managing pharmacy benefits.

“I spend a lot of time doing what you don’t get to do in a campaign, which is sitting with smart people, thinking longer thoughts, trying to have a fuller and more fleshed-out sense of the challenges facing the city and the country,” he said.

His regular schedule of “tutorials” with policy experts on issues like education, social entrepreneurism and job creation are helping him begin to craft his platform for next year. Though he is not yet ready to discuss many details, he is rehearsing them in speeches that grow out of these discussions.

Detailed ideas, like legislation to double the funding for summer jobs programs, are once again at the heart of Anthony Weiner’s mayoral campaign, though this time he is promoting them without as many jokes.

The overarching theme, though, remains looking out for “the middle class and those struggling to make it there,” the rhetoric he has been building on since first coining it in the 2005 race.

Weiner calls this vital to the fabric of the city.

“We have this ethos of aspiration,” Weiner said. “We really are the middle class capital of the world.”

Weiner saw that including in the middle class both those with middle class incomes and those who want to reach that level expands both the number of people included and the kind of policies they need. This was Weiner’s mini-revolution in Democratic thought, said Jim Kessler, a friend and another former Schumer aide who co-founded the progressive D.C.-based strategy center Third Way.

“A lot of Democrats don’t particularly understand the middle class, even though they think they do. Anthony’s one of those elected officials who truly does,” Kessler said.

The Congressional Middle Class Caucus, which Weiner created in April and has seen swelled to 37 members from both parties and 19 states, is just the latest move to make this, and not some supposed outer-borough allegiance, the defining characteristic of his political persona.

This is a natural progression: Weiner grew up in Brooklyn, the son of a teacher and a lawyer, and represented the old neighborhood for 14 years in the Council and Congress before his first run for mayor. He was middle class, his constituents were middle class, and he had spent his career in politics talking about middle class issues.

“Anthony is a guy who knows who he is. He knows where he came from, he knows what he believes in,” said Anson Kaye, a former chief of staff and Weiner’s communications director for the 2005 campaign. “I don’t think you could change him with a sledgehammer.”

By next year, all this will be part of an 11-year record in Congress to tout, a history of getting things done, or at least trying to, which he believes this time will convince New Yorkers that he is the man they should want in City Hall.

As with any legislative record, his will also provide potential avenues for attack. Around Father’s Day, for example, he was issuing press releases pushing for a new tax credit in response to a report that found a 12-percent rise in elderly parents being cared for at home between 2000 and 2006. Instead, what received attention was his bill creating a new visa category for models of a “distinguished reputation” looking to work in the United States.

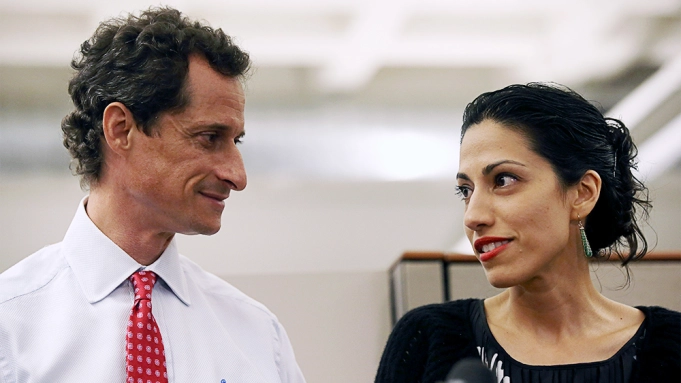

For a man whose dating life is already tabloid fodder and who is attempting to be seen as serious and as a champion of the common man, this was, at best, off-message.

At most, Weiner’s model bill would provide 790 visas under the new classification he would create. It is not a major piece of legislation, and does not seem likely to even be considered by the Senate anytime soon. Yet, for the better part of a week, the proposal was all over the news.

This is the danger of being the frontrunner in next year’s mayor’s race, which, like it or not, Weiner seems to be. He can draw crowds to his Sunday press conferences, even when they are just to publicize unsexy topics like reduced summer job funding, but everything he does is examined with increasing scrutiny, and every misstep or racy quote becomes potential front page news-yet another reason for a man with a naturally sharp tongue and lightning-fast wit to try to keep himself in check.

But there are benefits. Without an incumbent mayor seeking re-election and with a higher profile from his own performance in 2005 and since, Weiner had already raised more money for the ’09 campaign by this past January than he did for the entire ’05 run. He will very soon have collected enough to reach the campaign finance limit for the primary, though there is still almost a year and a half to go before the election.

“I’ve never had more money than the other guys,” he said. “I’m going to this time.”

This is new territory for Weiner, who has been the underdog throughout his political career-in his first race for Council, in his first race for Congress, in the minority in Washington and in the ’05 race. He has always figured out canny ways to use this to his advantage, whether by identifying with voters who feel like underdogs themselves or by brandishing it as proof that his are radical policy proposals. Back in early 2005, for example, when he was still grasping for the bottom of the polls, his lack of support was proof that he was preaching a hard truth about the need to cut waste and patronage.

“You may notice that I am not endorsed by political machines or big developers,” he said then. “I am proud of that.”

This time around, his record-setting fundraising is due in large part to significant real estate money, and most expect him to be endorsed by many more elected officials than the one Congressman, two Assemblymen and two major unions who supported him in 2005.

Weiner says he is glad to have the backing, and parses his phrasing from 2005.

“I wasn’t saying that I don’t honor Democratic clubs and institutions,” he said. “They’re valuable. They’re citizens. They care about the future of our city, too. I was trying to make the point: ‘Look, I’m running a different kind of campaign. My support is coming from entirely regular citizens who just get up everyday and try to make things go.'”

Without as much of a need to fundraise hanging over him, he will have time to build necessary relationships and court more support, both among the institutional powers and everyday New Yorkers. Already a frontrunner, Weiner will have more than a year to cement his lead.

But for all the chatter, the word he prefers to describe himself for 2009 is the same one he favored during the 2005 campaign: outsider.

Then, the word fit because he was behind in the polls and without much support. Now, according to his logic, it fits because he does not currently hold city office.

“I’m still fundamentally a guy trying to break into municipal politics,” he said. “I’m not a citywide elected official like Billy Thompson or Chris Quinn are.”

Asked to compare those two candidates to the field he faced in 2005, he resists, but uses a backhanded compliment to re-emphasize his point.

“Look,” he said, auditioning a phrase that seems almost certain to become a talking point for next year’s race, “these are two long-time fixtures of city government who have a lot to offer.”

Weiner sets up the contrast, likening himself to Bloomberg.

“I’m an outsider. I’m not a City Hall guy. I’m not someone who’s entrenched in city government. And if I’m able to be successful, I’m going to be able to have a level of independence to accomplish some of the things that he did. So I think that that’s one of the things about the Bloomberg years that people are going to honor, and they’re going to look for who it is that’s able to replicate them.”

“One of the ironies of the relationship with Mike Bloomberg,” he said, “is that I think I’m probably the most likely to be the one that he looks back at in a couple years and says, ‘You know what? He actually did a lot of the things I care about.'”

In 2005, Weiner ran against Bloomberg. For 2009, he seems to be preparing, in many ways, to run as the continuation of Bloomberg.

Bloomberg, though, has made no secret of how unimpressed he has been with Weiner over the years-as when, in March, he called Weiner’s suggestion that getting extra revenue from congestion pricing fees would have made getting money from Congress harder, “one of the stupider things I’ve ever heard said,” and, on further elaboration, “insanity.”

Weiner played down their disagreements, or the supposed feeling that he will be less eager to make the city an attractive place for new developers.

But he continues to make the argument that too many people have been left out of the equation in Bloomberg’s New York.

His biography, he said, will be the key. He is the candidate, he said, who will make “clear to the middle class and those struggling to make it that someone in City Hall is getting up every single day and rolling up their sleeves and saying, ‘I get your life. I understand the challenges that you face. I’m trying to deal with them.’”

Not that he is predicting a revolution, just more focus on the basics of the middle class platform: expanding affordable housing, improving schools and creating more and better jobs.

“I think for the most part, New Yorkers understand that their lives are not going to be transformed over night. There’s not going to be milk and honey running in the streets if I get elected,” he said. “I do want them to have a sense that when they listen to me that I understand their situation and come from a similar place.”

Overall, he said, he tends to agree with Bloomberg’s focus on big ideas and be very impressed with how the mayor has run the city. And he has been taking notes.

“One of the ironies of the relationship with Mike Bloomberg,” he said, “is that I think I’m probably the most likely to be the one that he looks back at in a couple years and says, ‘You know what? He actually did a lot of the things I care about.'”

Not that Weiner wants to be Bloomberg. For one thing, he is planning to take a more enthusiastic approach to the job.

“I hope that one of the things that people are going to see in the campaign and also if I’m fortunate enough to be mayor is that I’m going to do the job with a smile on my face,” Weiner said. “Sometimes it feels like Mike Bloomberg is getting a root canal when he’s in the Blue Room.”

Weiner has never been an executive, but he is a hard-charging, demanding boss who works around the clock and expects the same from his staff. When something goes wrong or takes longer than he believes it should, he is still prone to curse and throw phones-a factor that has contributed to a high staff turnover, with nearly 20 aides who have left since the beginning of this Congress alone.

He is still unabashed about speaking his mind, the “quintessential New Yorker,” said his fried Rep. Eliot Engel (D-Bronx/Westchester/Rockland) who recalled a fundraiser held at a Mets-Nationals game in Washington in May where Weiner berated Mets general manager Omar Minaya about team strategy.

“I remember thinking I wouldn’t be so forward with the general manager, but Tony didn’t care. He was just saying what was on his mind and not sugarcoating it. But that’s him. He’s brazen, he’s in your face,” said Engel, laughing over the memory.

But he knows this is not who he can be on the campaign trail over the next year. Being the jokester was fine for the almost parlor game Democratic primary in 2005, but actually getting people to think of him as executive means fewer wisecracks, fewer snappy one-liners.

Ed Koch, to whom Weiner is often compared in just about every way, remembers the problem well.

“David Garth gave me strict orders that I was not to be funny during the campaign. He thought I had to establish a statesman-like attitude,” Koch said, recalling the advice of his famed political consultant. “Garth said, and he was right, gravitas comes first. Humor-after they’ve accepted you as a substantial person.”

Weiner has not been to see Garth, and, by the accounts of several former staffers, has never formally addressed a strategy of trying to mute his sense of humor. But he has clearly internalized the need for a change.

This has been an odd adjustment for a man who has always relied on his natural political skills and knows that he is at his best when acting instinctually. He has always used humor to connect.

The problem, he fears, is people not understanding the vastly different views he takes of himself and his work.

“I’m a guy who doesn’t take himself terribly seriously but does take the challenges of the city very seriously,” he said. “I want to be someone people feel like they want to have a beer with or go to a Mets game with, but I also want people to feel that this is a guy who takes this stuff very seriously, who really every single day is thinking about ideas and trying to figure out how to implement them.”

His strength in 2005 was not his humor, but his ideas, he insisted, and the energy with which he was able to promote them. Those will not be reined in, he said, but expanded as he prepares to reintroduce himself to New Yorkers as a man they should want to be their next mayor.

Still, he can only change so much. Wisecracking, scrappy and self-deprecating tend to be the words people use to describe him, and no matter the money, no matter the poll position, no matter the efforts to appear more serious, he said, those will still apply.

“I think I’m going to be those things even if I try to tamp them down,” he said. “Weiner in ’09 is still scrappy and self-deprecating and everything else.”

A Trendy Friend, Same Middle Class Values

When Ben Affleck was cast in State of Play, an upcoming political thriller about a congressman whose mistress is murdered, he was not given much of a character description beyond “young, ambitious, star congressman.” But when he asked around about people who might fit this description, that was all he needed to point him in the direction of Anthony Weiner.

They had met once before, during the 2004 Democratic National Convention in Boston, when they ran into each other and Affleck told Weiner he was going to run against Rep. Michael Capuano (D-Massachusetts). Weiner, who shares an apartment in Washington with Capuano, gave Affleck a brusque response.

“That’s not such a great idea,” he said. “Stick to funny movies.”

But when they reconnected last year over the movie role, they immediately hit it off-though Weiner’s staff was worried at first.

“We got into a chest-to-chest shouting match over Obama-Clinton within about four minutes. Literally, people were outside the office wondering if they should go in and separate us,” Weiner recalled.

That has defined their relationship ever since.

“We kind of come from the same middle class: fighting is the sport of the thing. It was kind of the rhetorical version of HORSE,” Weiner said. “I left the room thinking, ‘He’s not the typical Hollywood guy.’ He left the room thinking, ‘He’s not the typical political phony.'”

For the most part, their friendship had been private. But on June 30, Affleck came to town to headline a fundraiser Weiner held at the trendy Meatpacking District restaurant Merkato 55. John Legend also attended, as did several models, local legal legend Sanford Rubenstein, singer/songwriter Duncan Sheik and Nicole Fiscella of Gossip Girl.

Weiner said that the event was almost too chic for him.

“They wanded me for hipness,” he joked.

He deflected the idea that this was a departure from his middle class message. In fact, he insisted, the creative arts crowd the event attracted were just the kind of people whom the city needs to start getting included in discussions of the middle class in the city.

“When I made remarks at that fundraiser, the first thing I said was how we need to save the middle class and make sure there’s affordable places for people to live. It was an applause line,” he said. “Just because you’re a photographer doesn’t mean you’re living in a $6,000-a-month apartment in SoHo.”

Nor does he worry about the impact it might have on his image.

“I don’t think there’s any chance of them looking at some fashionable guy in the Meatpacking District and confusing him for me,” he said. “I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

Average Rating