Bill O’Reilly was supposed to get out of politics.

He got hitched, became a step-father of two young girls and had a third of his own. No longer “the swinging New York bachelor,” as he put, O’Reilly decided politics was too kinetic a business for a responsible adult to keep.

That lasted about six months.

Maybe it was the charm of the underdog campaign. Or the grit of the slash-and-burn long-shot in the model of John Faso, who had hired O’Reilly for his 2006 gubernatorial campaign. Or maybe it was just a personal favor to State Senate candidate Liz Feld, who roomed with O’Reilly’s sister in college and who first lured O’Reilly back into the fray.

The former Manhattan GOP operative left the firm that bears his name, O’Reilly Strategic Communications, last year, selling his half to longtime partner Susan Del Percio and forswearing politics. He joined the communications shop of George Lence and Cristyne Nicholas, two former Rudy Giuliani associates who ran NYC & Company under both Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg.

O’Reilly’s portfolio was only supposed to include corporate and nonprofit clients. Despite their connections and backgrounds, the firm had no political ones.

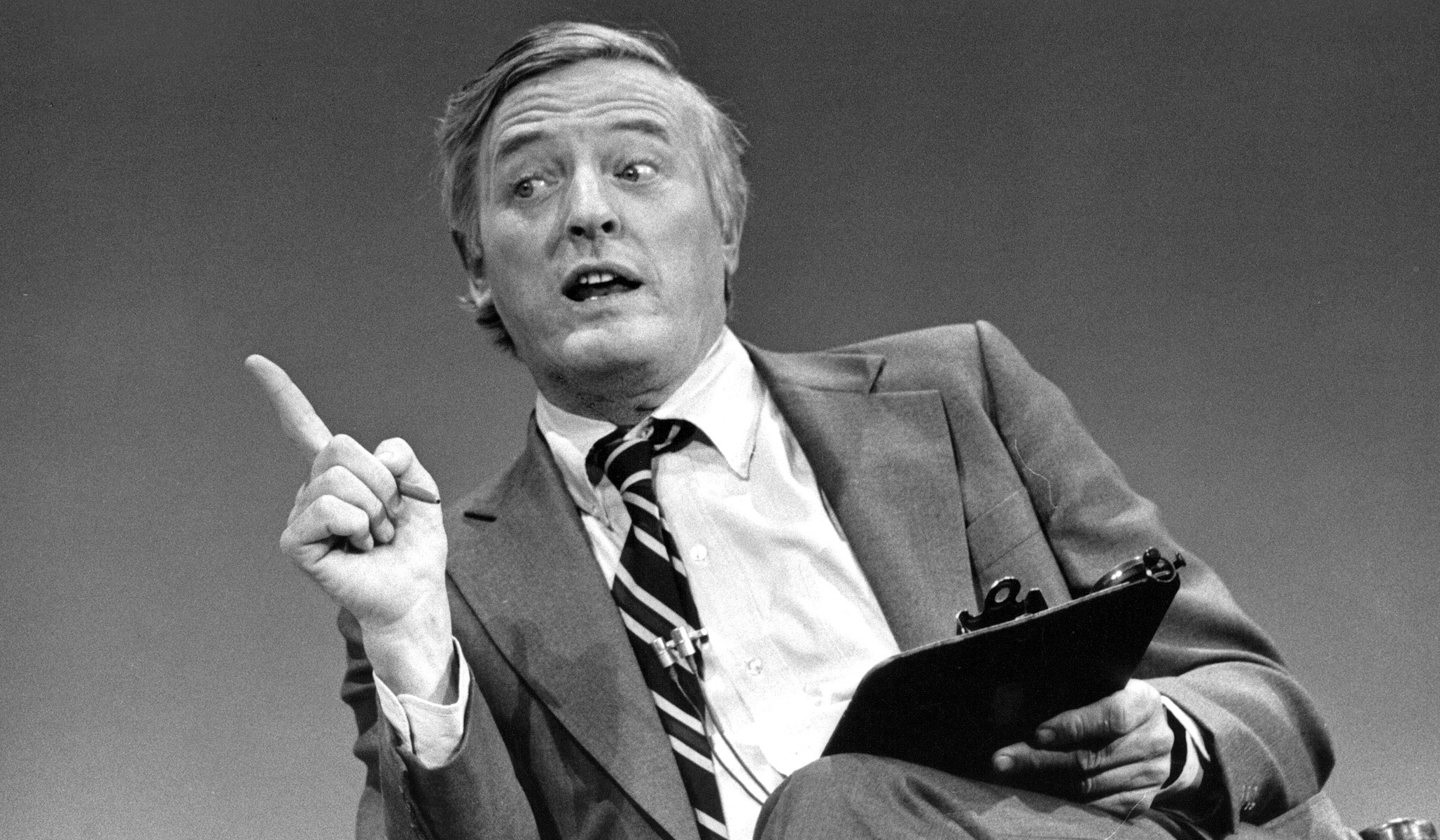

That did not feel quite right, said O’Reilly, a nephew of the late William F. Buckley and Sen. James Buckley (C), who cut his teeth decades ago as a wide-eyed Republican staffer to Upper East Side Sen. Roy Goodman, back when “Manhattan Republican” was not so laughable an idea.

So O’Reilly has spearheaded an effort at Nicholas & Lence Communications to piece together a separate political unit that is ramping up and preparing for 2010. He has plucked some new hires from the waves of GOP staffers leaving Albany. He even got his name onto the marquee, naming the new subsidiary NLO Strategies.

His first client was Feld, whom party leaders prize as one of their most promising talents. He is also working for Rob Astorino, a candidate for Westchester county executive, and Greg Camp, who raised eyebrows when he scored The New York Times endorsement in his 2007 Assembly run and is exploring a candidacy for Manhattan district attorney in the fall.

O’Reilly has won 22 races in his life—he keeps a tally, since so many people ask—and has lost plenty of others. But, perhaps out of necessity, the win-loss record is less important to O’Reilly than the profile of the candidate, the way he or she fits into the ever-shifting backdrop of New York politics.

“The whole state feels like it’s turning over,” he said, sitting at a conference table next to his 12th-floor office in the old New Yorker building in midtown. “There’s a sense, really, of urgency, that anyone who wants to be a player in the state, or has ideas for improving the state, should put them on the table.”

The phone keeps ringing, he said.

“We find a lot of people calling us and talking to us about how they want to reshape the state,” he said. “Five or six years ago, they probably wouldn’t have thought they had that opportunity.”

The feeling that this is a formative period in New York politics, that Republicans face self-reinvention or extinction, is not only what keeps O’Reilly wired, but what keeps his business thriving as well.

“There’s a lot of rethinking, a lot of reformulation, so there’s great opportunities out there,” he said. “When that happens, it’s important to have professionals around that know how to shape and communicate messages.”

Unlike some of the firms he competes with, O’Reilly can afford to be selective. Nicholas and Lence have made it clear that they do not want the political clients to crowd out the corporate ones, and NLO Strategies remains something of a side project for the three.

“The crux of our operation is our corporate nonprofit clients,” Lence said, adding that dabbling in politics “makes us sharper. It’s another tool in the arsenal.”

Their selectivity is also one of their main selling points to prospective clients. There are not many Republican consulting firms in downstate New York. The few that do exist, such as Mercury Public Affairs, rely much more heavily on their political base.

“We also don’t want to be a political mill,” Nicholas said. “There are a lot of companies that have grown so large, been bought out by other larger companies, that they become political mills. And they don’t really have any understanding, really, about which candidates they’re representing.”

O’Reilly is also widely regarded as someone even reporters like to deal with—an asset for a party whose media strategy can sometimes consist of blaming, mocking or downright bullying the press.

That habit of congeniality is a product mostly of the intellectual strain O’Reilly came up from. Though he is more moderate than either of his famous uncles, O’Reilly maintains a similar allegiance to the temperament and sensibility of conservatism.

That is why he has been willing to run, and lose, so many long-shot campaigns over the years, and why downstate Republicans continue to court him, especially now that they are looking to reshape themselves in the mold of all those practical, Manhattan conservatives whom O’Reilly toiled under for the bulk of his career.

“One of the great opportunities of today is that people are saying things that maybe haven’t been said for a long time,” O’Reilly said. “Whenever there’s turnover in the political world, ideas that have maybe been suppressed bubble up, and are said. And they’re important ideas.”

Average Rating