When Michael Bloomberg first arrived at City Hall, he moved his administration’s main offices into the old Board of Estimate chamber on the second floor. Rather than walls or offices, he and his top aides had work stations in the bullpen, the stock market floor interpolated into government.

In brick and mortar—or, rather, the lack of it—this was to be the symbol of Bloomberg’s approach to his new job. He was a businessman and a technophile, a man focused on communication and transparency, eager to bring change. That is who he was and is, and he planned to refashion city government to reflect it.

Along the way, he has created a style entirely his own, and one which observers agree is unlike that of any New York mayor to come before. It is a style that has four main elements, said Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at New York University: not personalizing conflict, having a government that “gets things done,” having a non-political set of productive appointees and making a concerted effort to maintain harmonious race relations.

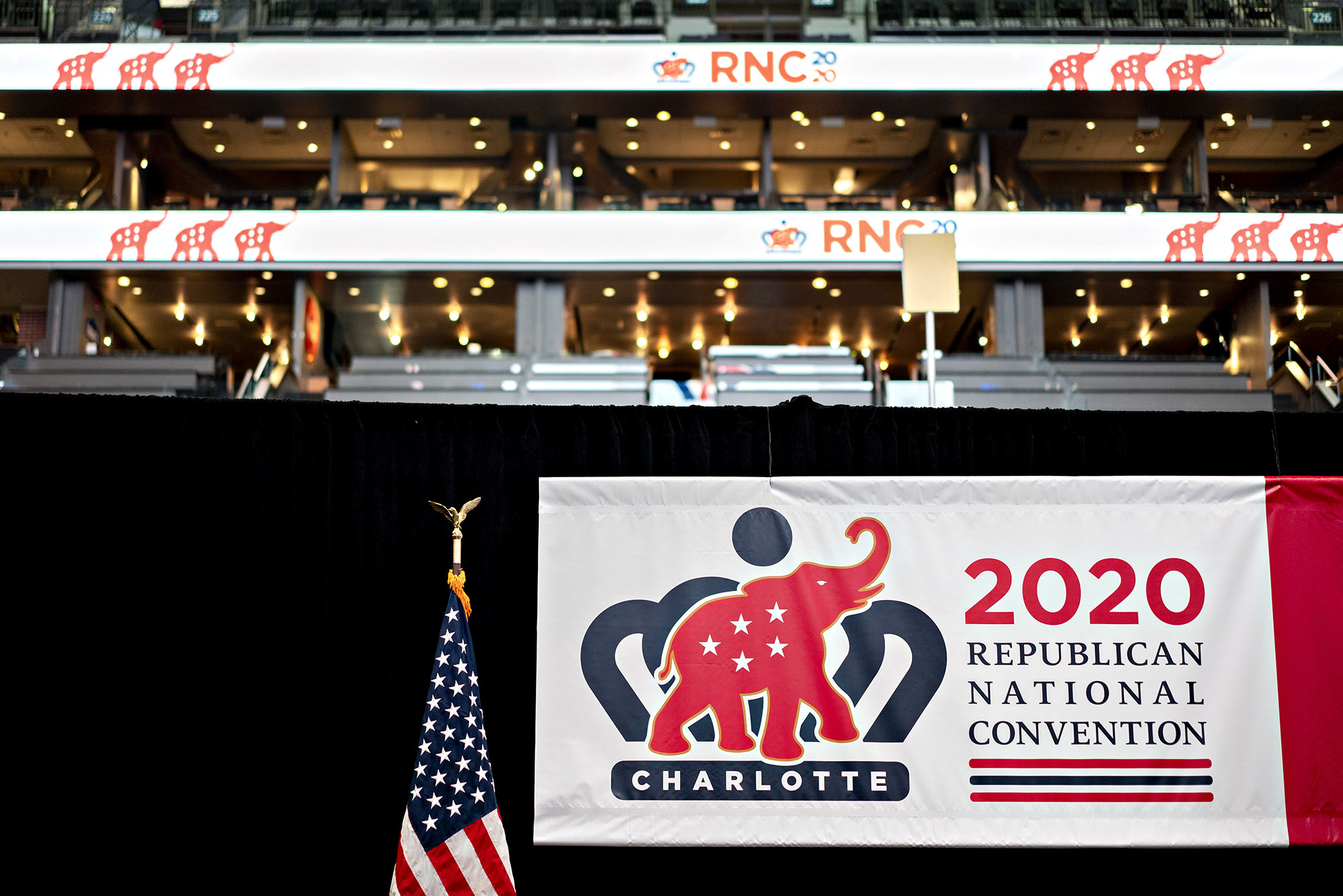

Their synthesis, Moss said, is what has enabled Bloomberg to do so much: the reorganization of the public schools, the continued decline in the crime rate, the diffusion in racial tension, the smoking ban, the ever-more popular 311—all of these successes bear the mark of Bloomberg. So, too, do the setbacks: the epic Olympic quest built around the sinking center of the West Side Stadium, the tensions between police and protesters during the 2004 GOP convention, the parents and teachers chafing at many of the changes to the schools, the scattered community and civic leaders complaining that the still-low crime rate reflects massaged statistics.

“This is about Mike Bloomberg’s approach to getting things done,” Moss said.

Still, an exact definition of the Bloomberg phenomenon is hard, if only because it continues to develop every day. But whatever it is, Moss and others insist, the Bloomberg phenomenon may very well have redefined the role of mayor for many years to come.

Neither “businessman-mayor” nor “technocrat-mayor” paint anywhere near a complete picture, argued Andrew White, director of the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs.

“In the sense that he is focused on the bottom line in both spending and revenues, that he is focused on results and uses data and outcome and performance-based contracting systems—all those things make him much more representative of corporate-style leadership,” White said.

Just as important, White explained, is the ideology that these techniques enable.

“One of the most interesting new elements with Bloomberg is that he’s shown that somebody with solid liberal values can be an effective administrator, an effective city leader, an effective mayor,” he said.

Bloomberg’s recruitment of private sector experts in lieu of patronage jobs—possible because his immense independent wealth enabled him to get to City Hall without amassing large political debts—has set a new standard for the city. The combination of delegating thorough responsibility to them and exhibiting ardent loyalty to his deputies once he does is another clear Bloomberg trademark, White said.

Taken together, that makes for something entirely distinctive from any easy epithet other than “his style,” White said.

“It is his style, and it is a style that has been generally effective,” White said.

Steven Malanga, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute who has previously taken the mayor to task for not adhering closely enough to fiscally conservative policies, also dismissed the simple “businessman-mayor” label, if only because there have not been enough businessmen elected mayor here or anywhere else in the country to make formulating such a model possible.

Though Malanga said former Mayor Rudy Giuliani (R), not Bloomberg, was most responsible for changing the mayoralty—Bloomberg had the luxury of continuing several successful, but once-controversial programs and policies which Giuliani had had to fight for first—Malanga also sees a clear Bloomberg stamp.

Much of this is the product of the mayor adjusting to the realities of governing and politicking in New York after riding in from the private sector, Malanga said. He is much more of a politician now than he was when he first campaigned in 2001, but he has retained his private sector sensibilities, resulting in a sort of outsider-insider minotaur that is Bloomberg, and Bloomberg alone.

“He began by saying that ‘we’re going to manage this just like a corporation, using the best people,’” Malanga said, describing the “learning curve” Bloomberg has climbed over the last four and a half years. “He quickly realized that the policy prescriptions are not hidden or magical or unknown, but they’re tough to carry out because you really need the political capital to carry them out. A place like New York needed to be reformed, it didn’t need to be smothered by policy wonks.”

Of course, Bloomberg almost never got the chance. Had it not been for the fluke circumstances of the 2001 election, the Sept. 11 attacks, the uncertainties in their wake and an auto-cannibalizing Democratic field, almost everyone agrees that he probably would not have won. In his first three years in office, Bloomberg exceeded almost all expectations, amassing the strength of a well-regarded incumbency to bring back to the voters last year. Unlike that of his immediate predecessor in City Hall, his was a style which relied less on moves that made front page headlines and more on policy initiatives likely to be buried deep in the back of the dailies—if they made it in at all. Especially for a man who has never inspired awe on the stump and who has rarely had a profile skip how visibly uncomfortable he looks on the campaign trail, this was not exactly the clear formula for a victory, let alone an overwhelming one.

“Bloomberg didn’t just create some new paradigm of businessman mayor or mayor slavishly devoted to issues,” explained Joseph Mercurio, a political consultant who counts both Republicans and Democrats among past clients. “That’s not what won him the election. What won him the election was being like that and having the money to tell people about it.”

According to Mercurio, then, anyone hoping to follow Bloomberg’s model of orientation towards policy over persona needs to have the money, and the willingness to spend it, in an election fight. Otherwise, Mercurio noted, the model will be Richard Ravitch, the businessman and former chair of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority who ran an outsider campaign built on policies and ideas in the 1989 Democratic primary. Without a personal fortune dumped into the bid, Ravitch came in fourth, behind three career politicians.

Given current media rates, Mercurio said, by 2009 running a modest general election campaign will mean “you need at least $10 million, and you really should be spending $15 million.”

This is possible by maxing out with public matching funds. A modest campaign may be enough for Democrats, who can count on the natural advantage of their overwhelming lead in party registration to help propel them through to November. Non-Democrats will probably need additional exposure to overcome that registration deficit, and that would mean more cash—which, in turn, would demand at least some degree of self-funding outside the campaign finance system.

There is no clear candidate to pick up that mantle, or the Bloomberg mantle in general. Richard Parsons, Jonathan Tisch and Dan Doctoroff have all been mentioned in some quarters as logical heirs, but each has repeatedly punted away the possibility of being in the race that will elect Bloomberg’s successor in 2009. And now that Henry Paulson, Jr. has moved to the Treasury Department, some are even eyeing Lloyd Blankfein, his replacement as Goldman Sachs Chairman and CEO. After all, the firm has a history before Paulson of sending people from his job into public service: Jon Corzine, the former senator and current governor of New Jersey.

Meanwhile, John Catsimatidis, owner of the Red Apple Group supermarkets chain, has intermittently fanned discussion of a run for years. Like Bloomberg, he says, he built up a successful business from scratch, and now he may want to try applying the same techniques which helped earn him a Gristedes fortune to the city as a whole. (Like pre-candidate Bloomberg, he is a well-known and well-connected Democratic donor, though, he says, not necessarily an absolutely committed one.)

“I have told my friends in the Republican Party that I would accept the nomination if offered to me and spend a lot of my own money to help New York continue to be the GREATEST city in the world,” he wrote in a recent email to friends and possible supporters. “If the dominoes are aligned properly … I have the desire to run.”

Schools Chancellor Joel Klein and Police Commissioner Ray Kelly, arguably the two most visible members of the administration after Bloomberg, could fit the mold of their current boss, but neither has the extensive personal wealth to bankroll runs. And Kelly in particular, whose name is discussed by political oddsmakers with enthusiasm, has done everything in his power to stamp down any speculation on the topic.

Among Democrats, Comptroller Bill Thompson has long been viewed as a sort of mayor in waiting, with the 2009 race as his for the taking. If he runs, he will likely benefit from being an African-American and well-liked in almost every quarter. But perhaps more importantly, he could benefit from fitting the Bloomberg mold of having a policy-oriented, financial background and what is often seen as a lackluster personality.

That would set him apart from most of the other Democrats whose names are circulating as possible 2009 contenders, from career politicians and public officials like Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum, Rep. Anthony Weiner and Council Speaker Christine Quinn. After eight years of Bloomberg, some think that the public could be wary of going back to the sort of career politician, flamboyant character mayors that the city elected for most of its current history.

Ed Koch (D) attacked this very tradition in his first mayoral race in 1977, using the slogan, “After eight years of charisma and four years of the clubhouse, why not try competence?”

It is perhaps a more apt slogan for Bloomberg 24 years later, though Koch insisted he delivered on it during his three terms and changed the role of mayor—though few would accuse him of dullness or his administration of lacking political intrigue.

The job has changed again with Bloomberg and will continue to change, reflecting the dynamism of the city that chooses the people to fill it.

“The city of New York will have different people with different expertise and different times in its life cycle,” Koch said. “At this particular moment, the personality and expertise of Michael Bloomberg is essential.”

So essential, Koch said, that one of Bloomberg’s inarguably lasting effects will be helping set a pattern of city voters alternating between politicians and business leaders in picking mayors in the future.

“Michael Bloomberg has established, by his immense ability and professionalism, that you don’t have to be somebody who has worked his way up in politics, different public offices to run a city if you are a first-rate administrator,” he said.

Moss, the NYU urban policy professor, added the caveat that since “we don’t know yet what will be the driving issues of the 2009 elections, or whether the character of our elections will go back to the normal party politics or whether there will be some change,” any predictions at this point are pure speculation.

But, he said, one thing is for certain: Bloomberg has changed the game.

“We’re not looking for City Hall to be run by entertainers or philosophers, but by people who care about making government work, people who care about the city,” Moss said.

So though future mayors may move back to the first floor and put up walls in the bullpen, they will likely not shake Bloomberg’s imprint on the building and all it houses for some time.

Now that Bloomberg has been there, “City Hall is not a theater,” Moss said. “It’s a place where things get done.”

Average Rating